What is beauty?

Humankind has pondered this monumental question for centuries. Millions of books, poems, songs, etc. have been written on the subject and will continue to be written. I am not going to attempt to answer this question here. Instead, I will explore the power that beauty has to elicit profound ‘spiritual’ epiphany.

Note: I am not a traditionally religious person, and I hesitate to use the word ‘spiritual’ because it’s meaning has been blunted by overuse and rendered somewhat impotent and open to misinterpretation. However, I believe that we can have profound experiences that open us up to the infinite riches of the universe. So, when I use the word ‘spiritual’ in this article, it is in this context.

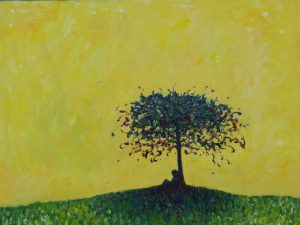

Beauty allows the possibility for us to transcend the mundanity of our lives and give us a glimpse of the eternal. The source of this experience can either be directly from nature, such as a flower, or created by a human, such as the drawings by Leonardo. This connection between beauty and the ‘spiritual’ elevates the artist’s role in society to one that has the potential to transform people’s lives.

Many thinkers throughout history have touched on this, for example, the playwright Eugene Ionesco said that ‘beauty is a manifestation of eternity’. Khalil Gibran wrote that ‘beauty is eternity gazing at itself in the mirror’.

Another artistic genius that I admire is the Russian film maker, Andrei Tarkovsky. His films are sublime philosophical explorations of the meaning of life. They feature long scenes of breathtaking visual beauty. In his book ‘Sculpting in Time’, he talks about how a beautiful image can invoke a ‘religious’ or ‘spiritual’ experience.

I will return to Tarkovsky shortly, but first, a little background.

I studied visual arts in the 1980s at a time when the idea of ‘beauty’ was unfashionable. The ‘art world’ was preoccupied with Post-Modernism and the deconstruction of ideas and belief systems. Conceptual Art was in fashion, and much of the resulting art work was devoid of any aesthetic quality. In fact, many artists actively avoided aesthetic considerations, preferring to shock, rather than seduce their audience. Artists whom aspired to make their work beautiful were often derided for being passé. It was considered by some that beauty was a distraction from the clarity of intellectual discourse, and because it had the power to seduce it wasn’t to be trusted.

A lot of the art at the time was intentionally ugly. It was a considered artful to spew on the canvas, or create sculptures from garbage. Galleries were filled with the rotting animal corpses. I understood the rationale behind some of these challenging and audacious artworks, but it was a confusing time for a young student who also wanted to create work that was pleasing to the eye. Since art school I have continued to make art, endeavouring to produce work that is both skilful and is aesthetically pleasing.

Tarkovsky talks about why he strives to create beautiful images in his films. His reasoning goes something like this:

Beauty is not a finite commodity. A beautiful image created today does not surpass all beautiful images yet to be created. When we are moved by a magnificent painting, we do not conclude that there will never be a painting as magnificent. When we are captivated by a sunset, we do not assume that it is the most beautiful sunset ever and will never be matched again. Of course not! There will be endless evenings when colourful skies will fill us with wonder. The same goes for flowers, butterflies, paintings, songs, or a smile on the face of a young child. Beauty can never be exhausted.

Tarkovsky’s reasoning continues as such; if beauty goes on forever it evokes in us a sense of the infinite. We are not only moved in that moment by the aesthetic qualities we perceive, but we are also moved by a manifestation of the eternal.

The idea of eternity is associated with religious experience; God is eternal, the everlasting spirit, and so on. Tarkovsky proclaims that when an artist creates an image of beauty, they elicit a ‘religious’ experience. Because beauty is inexhaustible, it invokes infinity and subsequently eternity. Beauty therefore belongs to the realm of religious experience.

What does this mean for us as human beings grappling with our corporeal existence and searching for meaning? I do not have a definitive answer to this question either, however, what I can say with conviction is that we need to allow ourselves to be arrested by beauty. To simply appreciate the beauty in the world around us. We need to move beyond the incessant analysis of the mind and allow our senses to tune in to the inexplicable beauty present in the universe.

Many people claim that beauty is subjective. They will argue that a painting by Monet is no more beautiful than a plastic toy mass-produced to be sold by fast food outlets. ‘It is my prerogative to say that the plastic toy is more beautiful than the Monet because it’s all just a matter of opinion.’ This is a commonly held belief that can undermine the value of serious artistic practice and appreciation.

To use a musical example, if someone was to play an out-of-tune violin, with no understanding of music, would the resulting noise be as beautiful as a Beethoven violin sonata played by an experienced violinist? Of course not! We may have call to admire other qualities of the untrained violinist, such as courage, spontaneity, or ambition, however, they will not possess the level of knowledge and skill to be able to create something refined enough to move our spirit.

Beauty is not passé or obsolete. It is an indispensable phenomenon with the power to transform our lives: Eternity gazing at itself in the mirror.